Materials and Methods, Pt. 2: An Aluminium Bow

For the final unit of the class, we were tasked with synthesizing one of our concepts from the previous four sections into a manufacturable set of parts. Then, with dimension drawings and cad work, we were to solicit quotes from manufacturers. These quotes would then be compiled and analyzed into a decision matrix and used to calculate top down and bottom up pricing.

The final form I went with was of the pure aluminium bow. I felt that it should be easy to solicit quotes on an object that is essentially a common stock piece and two rectilinear extrusions. This was a soon contested assumption

I made ten requests for quotes initially through companies with forms that allowed me to send the files right away. Three replied. Out of these three, two said that the design was not in their wheel house. The third, however, did give me a quote on their minimum order quantity.

Unsatisfied, I revised my approach. I redesigned my bow to be made of brass and utilize a simple bent shape. I then called 7 brass instrument manufacturers. The downside to this was that these companies were much smaller. I let them know I was a student so as not to lead them on. Only one of the people I called was willing to talk.

Mike, from West Side Machine Inc., helped me by talking through the different factors he uses to calculate price. These variables include the market price of bar stock, tooling and set up cost, the rate at which his machines run per hour, and then packing and shipping. Workers wages come from the tooling and set up cost since his mill is CNC.

I assigned weights based on what I deemed to be the most important factors to produce quality bows. I believed that a low MOQ was important for quality control and finish. I weighted this 30%. A manufacturer who could produce fewer items at high quality would have narrower tolerances. Then price was important so as not to price myself out of the competition. This was weighted 20%. Communication was the next most important at 15% weight. I based this on how well the manufacturer was at clearing ambiguity without solicitation. Then lead time and capabilities were equal at 10%. They should be able to deliver in a timely manner. And lastly helpfulness was 5%. Some of the people who I spoke with gave me insights about how this could be manufactured more economically.

With this information, I was able to calculate a weighted cost comparison between Tri-State Steel and West Side Machine Inc. While not a large sample size, it is perhaps indicative of how machining costs differ between large and small manufacturers in the United States. Moving forward with cost analysis on the top down and bottom up market models, I selected the quote from West Side Machine Inc.

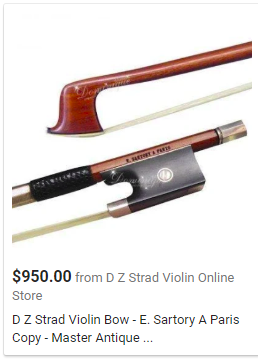

To calculate top down, I queried prices of the three major types of bows - Brazil wood, Carbon Fibre, and Pernambuco. Brazil wood bows were the least expensive, averaging about $65 a bow. Carbon fibre bows were mid tier, averaging $100 a bow.

Pernambuco was the most expensive. Although their were outliers both inexpensive - $70 - and expensive - $7,850- the more common prices averaged around $500. These variances take into account craftsmanship and materials, so I believe that my design would fall mid tier with the carbon fibre bows. Pricing around $100.

Using the bottom up method, my brass bow would cost approximately $4.49 to produce. This means I would need a sell price of at least $17.96 to produce a 75% gross margin. Given that this bow should sell at around $100, the actual gross profit margin would be approximately 96%.